We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely.

All art is quite useless.

Oscar Wilde, Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray

This attitude, which was once my own, might almost be defined as “using” pictures. […] In other words, you “do things with it”. You don’t lay yourself open to what it is, by being in its totality precisely the thing it is, can do to you.”

C.S. Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism

If we esteem only what is useful, what role does literature play in our lives? For reading fiction is useless unless it engenders the love of God. All imaginative works of beauty are useless in our modern conception of the word. But praise God for that.

Jessica Hooten Wilson, Reading for the Love of God

“I’m going to major in the humanities.”

“Why are you going to waste time on something useless? You should study something useful like business or STEM.”

The typical narrative around the humanities (or liberal arts, frequently used synonymously in error) is that they’re useless. They have no practical value, they don’t have immediately career paths other than teacher/professor in that field, they don’t solve big world problems, and they don’t lead to big paychecks. So why bother?

A lot of humanities boosters will respond to this proclaiming, no, the humanities ARE useful! They help build critical thinking skills! They make better communicators! They inculcate easily transferable soft skills that employers really like! These things are all true.

And yet, by allowing detractors to frame the question in terms of usefulness, we have acquiesced to the assumption that “useful” = “valuable” - an essentially utilitarian/pragmatic view of the world. It’s the dominant philosophy of our time and place, no doubt, but that doesn’t mean it’s the correct or only way to determine value.

Similarly, there are lot of defenses people make of books, literature, films, etc, that essentially involve their being useful for some purpose: increasing empathy, showing us experiences and viewpoints we wouldn’t otherwise have had, representing ourselves and others, making us better people, pushing political reform, etc. These kinds of arguments have been in the forefront this week, even, due to David Brooks’ recent NYTimes article about the power of art to change us. I’ve since seen no fewer than three responses to Brooks with three different takes just in my immediate feeds, approving, disagreeing, caveating. “What is art FOR?” we may ask. I’ll probably save more in-depth thoughts for another time, but I think this is the wrong question - it’s still utilitarian.

I’ve chosen to title this new venture “Useless Matters” because it’s a pleasing double-meaning pun that nevertheless gets into some ideas that I care about very deeply. I’m probably going to be writing about a lot of “useless” things here - the “matter” of this newsletter will be books, films, art in general, along with thoughts on teaching literature, that most gloriously useless of subjects. Useless things don’t matter much in a system based in utility, but the useless matters a great deal in one based in humanity.

Matters to Read

Compulsory Learning Just Does Not Stick - Joshua Gibbs at Circe Institute

The argument here is not that we shouldn’t require students to learn specific things, but that the things students read and experience (Gibbs is a literature teacher) at school are markedly different than the things they read and experience at home, and that this is because parents stop trying to form their children’s tastes at home but are fine allowing them to listen/watch/read anything that pleases them. This dovetails nicely (unsurprisingly) with Gibbs’ recent book Love What Lasts. As a high school teacher and the mom of a pre-teen, this is both preaching to the choir and also convicting!

If you don’t allow your children to blow out their senses on screens before they’re ten, you can give them Jane Austen novels to read when they’re eleven, and by the time British Literature rolls around junior year, there’s nothing compulsory about it. Every parent gets to decide just how compulsory Jane Austen, Mozart, and Michelangelo is going to feel in high school—it’s all in the way parents shape the tastes and habits of their children.

Dostoevsky’s Dangerous Gambit - Ryan Kemp at Hedgehog Review

Brilliant look at The Brothers Karamazov and what Dostoevsky is doing with the Rebellion and Grand Inquisitor chapters and, even more importantly, with the Father Zosima book. This is the heart of the novel in many ways and it depends, as argued here, on realizing that you can’t answer The Grand Inquisitor with logic. Dostoevsky gives us instead a response based on beauty. After all, as another Dostoevsky character says in another book: “Beauty will save the world.”

The great irony of the “Rebellion” chapter is that in its brutal success it primes readers to desire a response of an entirely different kind. We want a conventional refutation, something an especially clever student might manage after, say, a decade of doctoral work. But hopefully we can now see why this is misguided: Ivan explicitly disavows conventional argumentative approaches, and the potency of his appeal is directly tied to this refusal. If Dostoevsky wants to respond to Ivan in kind, he too must paint. He must show the reader that Christian love and forgiveness are more than sufficient to justify the existence of this world, even with all its horrors.

Choosing Consideration, Not Consumption by John Warner of the Biblioracle

John considers the larger cultural ramifications of Pitchfork closing. I would use the word “contemplation” rather than “consideration” but that betrays my classical education foreground. The point is the same - culturally we are getting rid of the idiosyncratic, the individual, and the learned opinions in criticism in favor of the algorithmic, and this is to our detriment. As John says in a follow-up post, “Is it too much to ask for a world where interesting writers write about interesting books interestingly?”

9 Ugly Truths About Copyright by Ted Gioia

Ted Gioia’s Substack has become my highest priority must-read these days. Whether it’s music or culture in general or even further afield topics, Ted is worth reading. This recent article is fairly sobering - we think copyright protects artists and creators but by and large this is not true.

Our Godless Era is Dead by Paul Kingsnorth

As always, fascinating and challenging reading from Kingsnorth.

What if a human being is not primarily a rational, bestial or sexual animal but in fact a religious one? By “religious” I mean inclined to worship; attuned to the great mystery of being; convinced that material reality is only a visible shard of the whole; able across all times and cultures and places to experience or intuit some creative, magisterial power beyond our own small selves. There is, after all, no current or historic culture on Earth that is not built around God, or the gods. None, that is, apart from ours.

Narnia Against the Machine: Deep Magic for the Modern Age - Natasha Burge at Front Porch Republic

Simply fantastic post showing how C.S. Lewis infused the medieval worldview, in which the world itself is rich with symbolism and meaning, into the Chronicles of Narnia. Both broad and deep. For more on this topic, look at Jason Baxter’s wonderful book The Medieval Mind of C.S. Lewis and for a LOT more, consider the Chronicles of Narnia miniclass at the House of Humane Letters.

Lewis’s appreciation for [the medieval] worldview was a cornerstone of his thought, so much so that he considered himself something of a displaced native of the medieval era. In the early decades of the twentieth century, at a time when literary modernism was in fashion and many of his academic peers pursued the overthrow of tradition, Lewis dedicated himself to keeping medieval wisdom alive. He approached the subject from many directions, highlighting its virtues in books, lectures, and sermons, but it was when Lewis guided readers through an enchanted wardrobe into a land of dancing dryads, an evil queen, and a lion who, while not at all safe, was unutterably good, that his quest reached its pinnacle. Under the guise of a winsome fairy tale, the heady atmosphere of Narnia is designed to allow readers to inhabit the medieval worldview.

Darwin, Bureaucratese and the Decline of Poetry - Aaron Ames at Circe Institute

This article is sparking a lot of thoughts in me that I’ll hopefully come back to at another time, but it is fascinating to me that poetry was what EVERY literate person primarily read until the 19th century. And now it’s almost only read when your English teacher makes you. Ames brings in ChatGPT and is the situation here really that AI can now write like humans, or that humans have begun to write like machines? Incidentally, in my recent experiments, ChatGPT cannot write blank verse, so maybe poetry is the answer. It was the way that the despotic machine in Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville was defeated. Is poetry in fact the thing that makes us human?

The lifeless, inarticulate, mechanistic language of bureaucracy is what all of society is being trained to value and regurgitate. Its imprint is found in every discipline of the academy. And it is most at home in the political and corporate world. It has become the very style of formal communication. One might even argue that it is our highest style of language, or, to be more precise, it is our sacred language. After all, the gods of today are mammon and machines, and what language is better suited to such inhumane idols? Where poetry once reigned, now bureaucratese!

Matters to Watch

Malcolm Guide is working on an Arthurian poem? EEEEEEEE!!!

I disagree with about half of this and am inspired by about half of it. Definitely has made me want to double down on annotation/commonplacing/note-taking even for books I’m not teaching. Which I do anyway, but not always consistently.

I might have a new obsession…and a fountain pen obsession is NOT cheap. Pray for restraint.

Matters to See

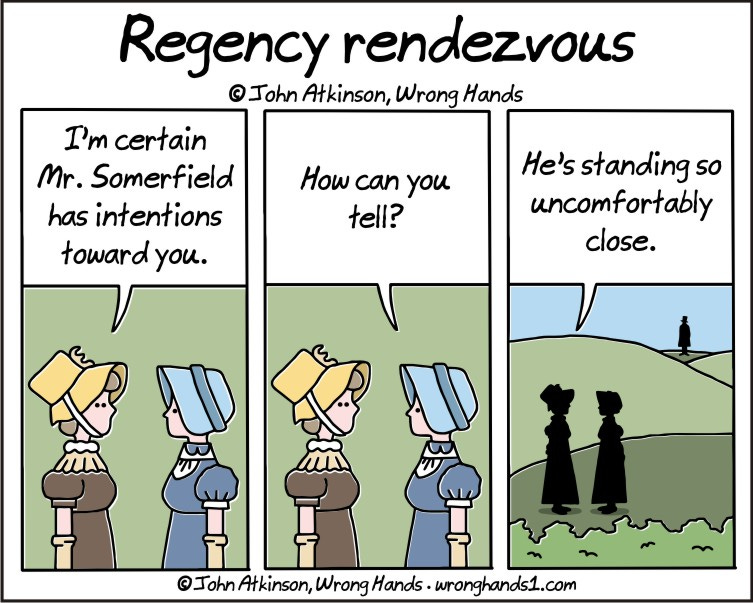

via Wrong Hands